GERD (chronic acid reflux)?

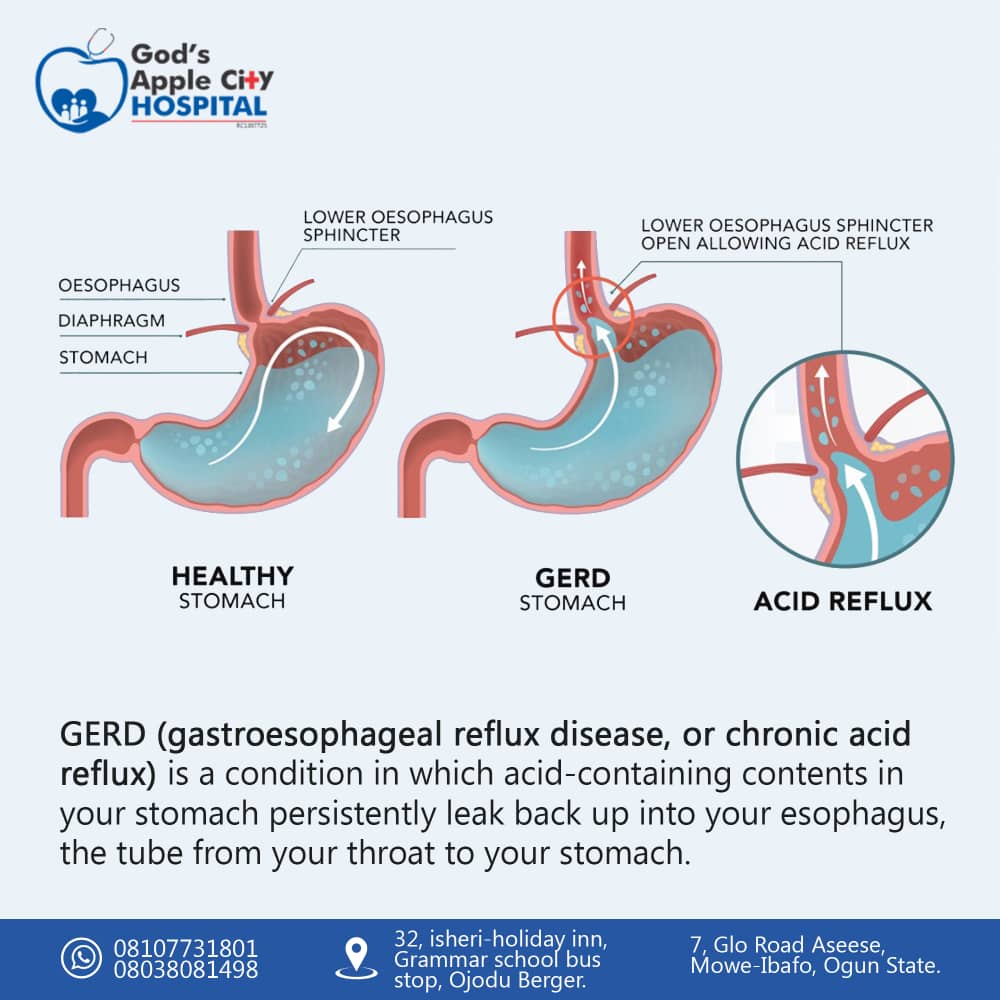

GERD (gastro esophageal reflux disease or chronic acid reflux) is a condition in which acid-containing contents in your stomach persistently leak back up into your esophagus, the tube from your throat to your stomach.

Acid reflux happens because a valve at the end of your esophagus, the lower esophageal sphincter, doesn’t close properly when food arrives at your stomach. Acid backwash then flows back up through your esophagus into your throat and mouth, giving you a sour taste.

What causes acid reflux?

Acid reflux is caused by weakness or relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (valve). Normally this valve closes tightly after food enters your stomach. If it relaxes when it shouldn’t, your stomach contents rise back up into the esophagus.

Factors that can lead to this includes:

- Too much pressure on the abdomen. Some pregnant women experience heartburn almost daily because of this increased pressure.

- Particular types of food (for example, dairy, spicy or fried foods) and eating habits.

- Medications that include medicines for asthma, high blood pressure and allergies; as well as painkillers, sedatives and anti-depressants.

- A hiatal hernia. The upper part of the stomach bulges into the diaphragm, getting in the way of normal intake of food.

Symptoms of GERD (chronic acid reflux)?

Different people are affected in different ways by GERD. The most common symptoms are:

- Heartburn.

- Regurgitation (food comes back into your mouth from the esophagus).

- The feeling of food caught in your throat.

- Coughing.

- Chest pain.

- Problem swallowing.

- Vomiting.

- Sore throat and hoarseness.

Infants and children can experience similar symptoms of GERD, as well as:

- Frequent small vomiting episodes.

- Excessive crying, not wanting to eat (in babies and infants).

- Other respiratory (breathing) difficulties.

- Frequent sour taste of acid, especially when lying down.

- Hoarse throat.

- Feeling of choking that may wake the child up.

- Bad breath.

- Difficulty sleeping after eating, especially in infants.

Is GERD (chronic acid reflux) dangerous or life-threatening?

GERD isn’t life-threatening or dangerous in itself. But long-term GERD can lead to more serious health problems:

- Esophagitis: Esophagitis is the irritation and inflammation the stomach acid causes in the lining of the esophagus. Esophagitis can cause ulcers in your esophagus, heartburn, chest pain, bleeding and trouble swallowing.

- Barrett’s esophagus: Barrett’s esophagus is a condition that develops in some people (about 10%) who have long-term GERD. The damage acid reflux can cause over years can change the cells in the lining of the esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus is a risk factor for cancer of the esophagus.

- Esophageal cancer: Cancer that begins in the esophagus is divided into two major types. Adenocarcinoma usually develops in the lower part of the esophagus. This type can develop from Barrett’s esophagus. Squamous cell carcinoma begins in the cells that line the esophagus. This cancer usually affects the upper and middle part of the esophagus.

- Strictures: Sometimes the damaged lining of the esophagus becomes scarred, causing narrowing of the esophagus. These strictures can interfere with eating and drinking by preventing food and liquid from reaching the stomach.

Diagnosis

Your doctor might be able to diagnose GERD based on a physical examination and history of your signs and symptoms.

To confirm a diagnosis of GERD, or to check for complications, your doctor might recommend:

- Upper endoscopy. Your doctor inserts a thin, flexible tube equipped with a light and camera (endoscope) down your throat, to examine the inside of your esophagus and stomach. Test results can often be normal when reflux is present, but an endoscopy may detect inflammation of the esophagus (esophagitis) or other complications. An endoscopy can also be used to collect a sample of tissue (biopsy) to be tested for complications such as Barrett’s esophagus.

- Ambulatory acid (pH) probe test. A monitor is placed in your esophagus to identify when, and for how long, stomach acid regurgitates there. The monitor connects to a small computer that you wear around your waist or with a strap over your shoulder. The monitor might be a thin, flexible tube (catheter) that’s threaded through your nose into your esophagus, or a clip that’s placed in your esophagus during an endoscopy and that gets passed into your stool after about two days.

- Esophageal manometry. This test measures the rhythmic muscle contractions in your esophagus when you swallow. Esophageal manometry also measures the coordination and force exerted by the muscles of your esophagus.

- X-ray of your upper digestive system. X-rays are taken after you drink a chalky liquid that coats and fills the inside lining of your digestive tract. The coating allows your doctor to see a silhouette of your esophagus, stomach and upper intestine. You may also be asked to swallow a barium pill that can help diagnose a narrowing of the esophagus that may interfere with swallowing.

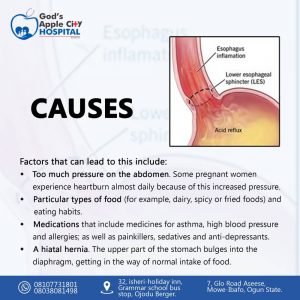

Treatment

Your doctor is likely to recommend that you first try lifestyle modifications and over-the-counter medications. If you don’t experience relief within a few weeks, your doctor might recommend prescription medication or surgery.

Over-the-counter medications

The options include:

- Antacids that neutralize stomach acid. Antacids, such as Mylanta, Rolaids and Tums, may provide quick relief. But antacids alone won’t heal an inflamed esophagus damaged by stomach acid. Overuse of some antacids can cause side effects, such as diarrhea or sometimes kidney problems.

- Medications to reduce acid production. These medications — known as H-2-receptor blockers — include cimetidine (Tagamet HB), famotidine (Pepcid AC) and nizatidine (Axid AR). H-2-receptor blockers don’t act as quickly as antacids, but they provide longer relief and may decrease acid production from the stomach for up to 12 hours. Stronger versions are available by prescription.

- Medications that block acid production and heal the esophagus. These medications — known as proton pump inhibitors — are stronger acid blockers than H-2-receptor blockers and allow time for damaged esophageal tissue to heal. Over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors include lansoprazole (Prevacid 24 HR) and omeprazole (Prilosec OTC, Zegerid OTC).

Prescription medications

Prescription-strength treatments for GERD include:

- Prescription-strength H-2-receptor blockers. These include prescription-strength famotidine (Pepcid) and nizatidine. These medications are generally well-tolerated but long-term use may be associated with a slight increase in risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency and bone fractures.

- Prescription-strength proton pump inhibitors. These include esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), omeprazole (Prilosec, Zegerid), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (Aciphex) and dexlansoprazole (Dexilant). Although generally well-tolerated, these medications might cause diarrhea, headache, nausea and vitamin B-12 deficiency. Chronic use might increase the risk of hip fracture.

- Medication to strengthen the lower esophageal sphincter. Baclofen may ease GERD by decreasing the frequency of relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter. Side effects might include fatigue or nausea.

Surgery and other procedures

GERD can usually be controlled with medication. But if medications don’t help or you wish to avoid long-term medication use, your doctor might recommend:

- The surgeon wraps the top of your stomach around the lower esophageal sphincter, to tighten the muscle and prevent reflux. Fundoplication is usually done with a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure. The wrapping of the top part of the stomach can be partial or complete.

- LINX device. A ring of tiny magnetic beads is wrapped around the junction of the stomach and esophagus. The magnetic attraction between the beads is strong enough to keep the junction closed to refluxing acid, but weak enough to allow food to pass through. The LINX device can be implanted using minimally invasive surgery.

- Transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF). This new procedure involves tightening the lower esophageal sphincter by creating a partial wrap around the lower esophagus using polypropylene fasteners. TIF is performed through the mouth with a device called an endoscope and requires no surgical incision. Its advantages include quick recovery time and high tolerance.

If you have a large hiatal hernia, TIF alone is not an option. However, it may be possible if TIF is combined with laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

https://web.facebook.com/Godsapplecity

read other blogs https://godsapplecityhospital.com/breast-cancer-signs-and-detection/